Written by : Fuji Riang Prastowo

(Meditation Practitioner for Interfaith Community; Assistant Professor in Sociology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia ; email : fujiriangprastowo@ugm.ac.id)

Context: Stillness Before Insight

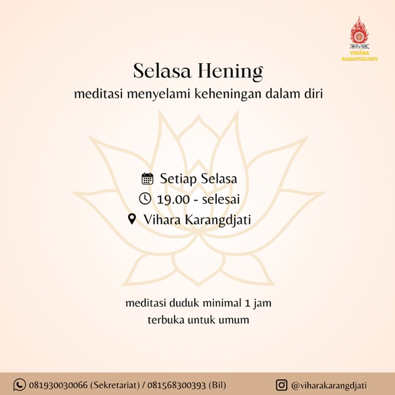

On Tuesday evening, May 6th, 2025, I was invited to lead the weekly Selasa Hening session at Vihara Karangdjati, Yogyakarta. It’s a gentle interfaith gathering where participants from diverse traditions sit together in silent samatha meditation for a full hour—no chanting, no instructions, just breathing and awareness.

After the stillness, I offered a Dhamma reflection drawn from my ongoing study of the Manual Abhidhamma, specifically the section on consciousness (Citta), available at dhammavihari.or.id. The topic I chose felt particularly relevant—not only to meditative life but to ordinary moments where craving subtly disguises itself as joy.

I spoke about a particular type of unwholesome consciousness:

Lobha-Mūla Citta – Somanassa-sahagata, Diṭṭhi-sampayutta, Asaṅkhārika — a moment of mind rooted in greed, accompanied by mental pleasure and wrong view, arising spontaneously without invitation.

What struck me most—and what I shared that evening—was how familiar this mind can feel. It shows up in daily life and even in meditation, often unrecognized. It doesn’t shout; it smiles. It doesn’t fight; it persuades. And that’s precisely what makes it powerful.

Prologue: Gentle Desires and Misguided Beliefs

In the current of daily life, there are moments when a sudden desire arises—smooth, persuasive, and often accompanied by a sense of joy. Thoughts like, “I deserve this,” or “This is happiness, this is life,” can surface without invitation. Such moments may feel harmless, even healthy. After all, what could be wrong with wanting something that brings pleasure?

Yet, beneath that lightness, a subtle form of mental activity is at play—one that the Buddhist Abhidhamma tradition describes with astonishing precision. It is a type of unwholesome consciousness that seems benign but pulls the mind away from clarity and freedom. In Pāli, it is known as:

Lobha-Mūla Citta – Somanassa-sahagata, Diṭṭhi-sampayutta, Asaṅkhārika—

a consciousness rooted in greed, accompanied by joy, entangled with wrong view, and arising spontaneously.

The Nature of This Mind: Sweet on the Surface, Misleading at Its Core

This form of consciousness has a particular signature: it arises without effort, carries an emotional sweetness (somanassa), and is underpinned by a distorted view (diṭṭhi). No one asks for it to appear; it does so on its own—automatically, from latent mental habits. In Abhidhamma, this is termed asaṅkhārika—a spontaneous mental event not triggered by external suggestion.

What makes it dangerous is its pleasantness. It feels good, and therefore it seems right. The accompanying wrong view silently affirms the belief that happiness can be secured through possession, pleasure, or status. This is not overt craving or violent grasping—it is refined clinging, wrapped in self-justifying narratives that the mind cannot easily detect as suffering.

The Structure of Consciousness: Sweet on the Surface, Misleading Within

In Abhidhamma, every moment of consciousness (citta) arises alongside specific mental factors (cetasika). For this particular type, the defining components are:

| Element | Meaning |

| Lobha | Craving or attachment toward an object perceived as pleasing |

| Somanassa | Joyful or mentally pleasant feeling |

| Diṭṭhi | Wrong view, such as believing that true happiness lies in ownership or worldly experiences |

| Asaṅkhārika | Arising spontaneously, not prompted by external influence, but from the mental continuum itself |

This consciousness frequently appears in daily life without invitation—as if the mind reflexively thinks, “This matters,” or “This will make me happy,” or “This is part of success.”

This type of consciousness manifests in various everyday situations:

- When seeing a luxury item and a spontaneous thought arises: “I must own this to appear successful.”

- While enjoying delicious food, thinking: “This is heaven; this is the meaning of life.”

- Upon hearing someone else’s success, feeling an urge to surpass them.

- During casual conversations, subtly justifying dishonest behavior for personal gain.

The common thread in all these moments is that the thoughts arise unprovoked—accompanied by pleasant feelings that reinforce distorted beliefs.

Everyday Appearances: Patterns that Go Unnoticed

This consciousness plays out subtly in daily life. A person passes by a luxury store and suddenly thinks, “That watch would complete me.” Another enjoys a lavish meal and feels, “This is heaven; this is the point of life.” Upon seeing a friend’s success, a subtle impulse arises to compete or outperform—not from inspiration, but from egoic hunger.

Such thoughts are not provoked by others. They arise internally, automatically. They are pleasurable and accompanied by a narrative that justifies them—hallmarks of Lobha-Mūla Citta in this particular form. The mind doesn’t question them because they don’t appear harmful. In fact, they often masquerade as motivation or joy.

The Western Mirror: Impulsivity and Cognitive Distortion

In Western psychology, such patterns are echoed in terms like impulsivity, hedonic drive, and cognitive distortion. When the mind believes “I’ll only be happy if I get this,” it’s enacting a distorted thought pattern. When one acts without pause, driven by emotional gratification, it’s seen as impulsive or narcissistically motivated.

Yet where modern psychology focuses on behavior and thought content, Abhidhamma speaks of the very nature of the consciousness itself. This is not merely a thought—it is a specific moment of mind woven with craving, delusion, and wrong view. It is not created in the moment; it is inherited from past conditioning, ready to arise when mindfulness lapses.

Contemporary psychology recognizes such mental patterns as:

- Impulsivity: quick actions without deep consideration, driven by emotional urges.

- Narcissistic gratification: a need to feel special through external accomplishments or possessions.

- Cognitive distortion: flawed thought patterns like, “I must have this to be happy.”

However, unlike Western psychology which often frames these as behavioral disorders or thought errors, Buddhist psychology sees them as specific moments of consciousness—a dynamic interplay of emotion, perception, attachment, and false view occurring in the very fabric of the mind.

Why This Consciousness Arises

The roots of this mind-state go deep. Texts in the Abhidhamma and its commentaries explain that such consciousness arises due to karmic momentum—the force of past intentions saturated with craving and wrong view. When mindfulness is absent, the momentum of habit (santāna) carries this citta to the surface.

Modern life makes it even easier. Consumerism, social media, and constant comparison feed the tendency. Without meditative discipline or moral introspection, this type of citta becomes the default mode. Even in spiritual practice, if one is not watchful, this consciousness can resurface in more subtle forms, supported by one’s underlying bhavaṅga—the flow of subconscious mental activity rooted in past lives.

This form of consciousness doesn’t appear randomly. The Abhidhamma and its commentaries offer several deep-rooted causes:

| Cause | Explanation |

| Past kamma | Mental tendencies shaped by previous actions rooted in attachment |

| Consumerist environment | Constant exposure to materialistic values that glorify pleasure and possession |

| Lack of mental training | Without mindfulness or moral cultivation, the mind defaults to automatic habits |

| Bhavaṅga | The subconscious flow of mental continuity (background consciousness) shaped by past life tendencies |

This consciousness often arises when the mind is unguarded—such as when relaxed, tired, or daydreaming. Its emergence is subtle, yet persistent.

Meditation Disrupted: When Pleasure Masquerades as Progress

In meditation, this type of mind can subtly derail progress. It doesn’t crash the practice with distraction or aversion. Instead, it arrives wrapped in peaceful sensations or uplifting thoughts. One may begin to think, “This must be jhāna,” or feel spiritual pride, believing one has advanced far on the path. Yet what’s truly present is clinging—to the calm, to the pleasure, or to the identity of being a meditator.

This mind doesn’t disrupt meditation through agitation, but through attachment to what feels good. Concentration remains, but the object of meditation has quietly shifted. The meditator no longer follows the breath or the kasina but becomes absorbed in the sensation or fantasy. What arises is micchā-samādhi—wrong concentration—accompanied by delusion and subtle ego.

In samatha meditation practice, this form of consciousness can manifest in very subtle ways:

- As a pleasurable feeling that clings to bodily sensations.

- As a belief that spiritual attainment has occurred—when in fact, it’s an illusion.

- As pleasant thoughts that quietly distract from the primary object of meditation.

Its presence obstructs the deepening of concentration (jhāna) and, more dangerously, feeds spiritual ego or spiritual bypassing—the mistaken belief that one has “progressed” in the Dhamma simply because the experience feels pleasant or peaceful.

Transforming the Pattern: Strategies from the Dhamma

To work skillfully with this type of consciousness, one must bring both insight and structure into the practice. Asubha bhāvanā, or contemplating the unattractive nature of things, helps weaken attachment to pleasant forms. Observing vedanā (feeling) as merely arising and passing, without grasping, dissolves the illusion of permanence in pleasure.

Wrong views are undone not by force, but by steady exposure to right view—through study, reflection, and dialogue with wise companions (kalyāṇamitta). The practice of cittānupassanā—observing the mind itself—enables recognition of this citta the moment it arises. With mindfulness (sati), one can note: “This is desire,” or “This is a mind with wrong view,” and not act upon it. Thus, it passes like a cloud, ungrasped.

To weaken the influence of this consciousness, several Dhamma-based approaches can be applied:

| Aspect | Strategy |

| Lobha | Practice asubha bhāvanā (contemplating the unattractive or impermanent nature of objects) |

| Somanassa | Apply Satipaṭṭhāna on feelings: observe vedanā without clinging |

| Diṭṭhi | Cultivate right view through Dhamma study and discussion with kalyāṇamitta (spiritual friends) |

| Asaṅkhārika | Practice cittānupassanā—observing the mind’s movements clearly as they arise |

| Weak concentration | Strengthen ekaggatā (one-pointedness) through breath meditation (ānāpānasati) or visual objects (kasina) |

The key is direct recognition of the consciousness the moment it arises—not pushing it away, not indulging it, simply seeing it and letting it dissolve without reaction.

Conclusion: When Sweetness Is Not Freedom

This form of consciousness does not come with warning signs. It doesn’t shout; it whispers. It appears as a friend, offering joy, motivation, or comfort. Yet it quietly leads the heart into clinging and subtle delusion. Left unexamined, it tightens the cycle of becoming. But seen clearly, it becomes a powerful teacher.

In a world where “more is better” and pleasure is marketed as truth, recognizing Lobha-Mūla Citta – Somanassa-sahagata, Diṭṭhi-sampayutta, Asaṅkhārika is a quiet act of rebellion—and liberation. The recognition that not all joy is wise, and not all desire is freedom, opens the gate to true discernment.

This is not about suppressing joy, but about seeing joy without illusion. It is not about rejecting desire, but knowing its nature. In that clarity, the mind begins to release itself—gently, wisely, and without regret.

Yogyakarta, 6 May 2025

References

Anuruddha, Ā., Bhikkhu Bodhi (Trans.), Nārada, M. T., Revatadhamma, B., & Sīlānanda, S. U. (1993). A comprehensive manual of Abhidhamma: The Abhidhammattha Sangaha of Ācariya Anuruddha. Buddhist Publication Society.

https://www.google.co.id/books/edition/A_Comprehensive_Manual_of_Abhidhamma/hxopJgv85y4C?hl=en&gbpv=0

Kheminda, A. (2024). Manual Abhidhamma: Kesadaran. Dhammavihari Buddhist Studies. https://www.dhammavihari.or.id/ebook

Kyaw Min, U. (1980). Buddhist Abhidhamma: Meditation and concentration. Burma Buddhist Meditation Center.

https://www.google.co.id/books/edition/Buddhist_Abhidhamma/Dy_YAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&bsq=abhidhamma%20for%20meditators

Nyanaponika, T. (1998). Abhidhamma studies: Buddhist explorations of consciousness and time. Wisdom Publications.

https://www.google.co.id/books/edition/Abhidhamma_Studies/1q41cMYoWDMC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Leave a comment